Raising a Child With ADHD: Practical Parenting Strategies That Help

It’s 7:40 AM. Shoes are missing. The bus is coming. Your child is crying, and you’re already exhausted.

Before the day has properly begun, you’ve negotiated, reminded, repeated yourself, raised your voice, felt guilty about raising your voice, and quietly wondered why everything feels harder in your house than it seems to be for everyone else.

Many parents of a child with ADHD carry silent fears they rarely say out loud:

“I’m failing my child.”

“Other parents seem to manage this better.”

“Why does simple parenting feel so complicated for us?”

For many parents, a diagnosis raises urgent questions. What causes ADHD? How does it affect a child’s behavior, health, and school life? And most importantly, how can parents help a child with ADHD succeed without constant conflict or burnout? This guide answers those questions with clarity, science, and compassion.

Key Learnings

- ADHD is a neuro-developmental condition.

- Clear expectations, routines, and positive reinforcement support good behavior more effectively than punishment.

- Emotional dysregulation is a central part of ADHD and affects both children and parents.

- With early intervention, parent training, and consistent support, many children with ADHD can succeed at school and in life.

What Is Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder?

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder is a neurodevelopmental condition that affects how the brain manages attention, impulse control, activity level, and emotional regulation. ADHD is often described as a polymorphic condition, meaning it can look very different from one child with ADHD to another.

Some children with ADHD primarily struggle with inattention. Others show more hyperactivity or impulsivity. Many experience a combination of these symptoms. This explains why parenting one child with ADHD can feel completely different from parenting another.

ADHD is strongly influenced by genetic factors. Prenatal and early neurological influences may also contribute to ADHD, which typically begins in childhood before age 12 and often persists into adolescence and adulthood, even if symptoms change over time.

How ADHD Was First Identified

In 1798, Scottish physician Alexander Crichton described children who struggled to sustain attention from an early age. In 1902, Sir George Frederick Still documented impulsivity and difficulties with self-control in children with normal intelligence.

In 1937, physician Charles Bradley observed that stimulant medication improved attention and behavior. Although initially overlooked, this finding later shaped modern ADHD medication approaches.

Today, ADHD treatment is typically comprehensive and multimodal and may include behavioral parent training, school accommodations, psychotherapy, skills development, and medication when appropriate.

ADHD Symptoms in Children

ADHD is one of the most common attention disorders in childhood. In the United States, approximately 7 million children aged 3 to 17 have been diagnosed with ADHD.

Boys are diagnosed more often than girls, with around 15% of boys and 8% of girls receiving a diagnosis. Girls are often underdiagnosed because symptoms may present as inattention rather than disruptive behavior.

Inattention

- Difficulty paying attention

- Making careless mistakes

- Trouble following instructions

- Losing items needed to complete tasks

- Difficulty with task completion.

Hyperactivity

- Constant movement or restlessness

- Difficulty sitting still

- Excessive talking

- Fidgeting or pacing.

Impulsivity

- Interrupting others

- Acting without thinking

- Difficulty waiting for turns.

Symptoms must appear in more than one setting, such as home and school, and must significantly interfere with daily functioning. This helps distinguish ADHD from situational challenges or temporary stress responses. A child may manage well in one environment but struggle in another, which is why information from parents, teachers, and caregivers is often essential for understanding the full picture.

Co-morbid Conditions in Children With ADHD

Some children with ADHD experience additional challenges that affect behavior, learning, and emotional health. These co-occurring conditions may include:

- learning disabilities

- tic disorders

- speech or language difficulties

- behavioral disorders

- autism spectrum conditions

- anxiety or phobic disorders

- depressive disorders.

These conditions are known as comorbidities. They can make ADHD more complex to identify and manage because some symptoms overlap, while others may be separate from ADHD itself.

For some children, certain symptoms lessen as they grow older. However, many continue to experience difficulties into adulthood, particularly with attention, organization, impulse control, and emotional regulation. These challenges can affect work performance, relationships, and overall quality of life.

For example, parenting a child with ADHD and dyslexia can bring additional challenges related to learning, reading, and self-esteem, often requiring coordinated support at home and at school. Likewise, parenting a child with ADHD and autism may involve supporting differences in communication, sensory processing, and emotional regulation alongside attention-related challenges.

When other conditions are present, symptoms of ADHD may feel more intense and persistent. Coordinated support involving parents, teachers, and healthcare professionals is often essential to help children and adults manage their needs effectively.

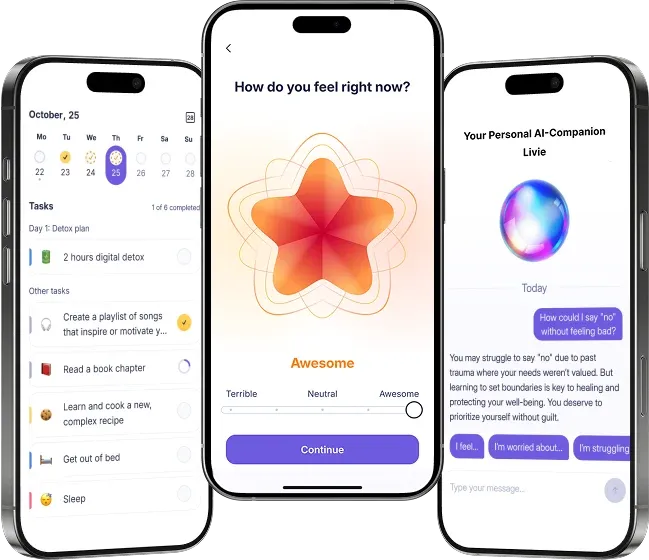

A research-informed ADHD test can be a helpful starting point for understanding symptom patterns.

ADHD Across Developmental Stages

ADHD does not look the same at every age.

- Younger children may show more hyperactivity and impulsivity.

- School-age children often struggle with attention, organization, and their sense of self.

- Adolescents may struggle to regulate their emotions, cope with academic stress, and navigate identity challenges.

- Understanding how ADHD evolves helps parents adjust expectations and parenting strategies over time.

With early intervention, parent training, school support, and emotional understanding, a lot of children with ADHD grow into adults who manage symptoms effectively.

Supportive parenting reduces risks related to academic difficulties, low self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and relationship challenges.

How ADHD Affects Family Life

Living with a child with ADHD can place an ongoing strain on families. Parents describe emotional exhaustion, frequent conflict, and uncertainty about how to respond to their child’s behaviors.

Children with ADHD often struggle with emotional dysregulation, which can affect the entire household. Without consistent strategies, stress can accumulate and strain relationships over time.

This is why parent training is frequently recommended. Parent training helps caregivers learn predictable, evidence-based responses that improve behavior while reducing guilt and burnout.

ADHD and School Life

School places heavy demands on paying attention, organization, self-control, and task completion. Children with ADHD may struggle with sitting still, following classroom rules, completing assignments, or managing time.

Parents can support their child's success at school by maintaining regular communication with their child’s teachers, advocating for necessary accommodations, and considering an individualized education plan when appropriate.

Parents can support their child’s school experience by maintaining regular communication with their child’s teacher, advocating for necessary accommodations, and considering practical strategies to help children with ADHD succeed in school that involve structured support and classroom adjustments.

ADHD and a Child’s Self-Esteem

Repeated negative feedback can have a lasting impact on a child’s self-esteem over time. Children with ADHD often receive more criticism than their peers, even when they are trying hard.

Encouragement and focusing on strengths help protect mental health and confidence.

How Parents Can Help a Child With ADHD

Parenting a child with ADHD requires a different approach, not more effort. The goal is to support behavior, learning, and emotional safety.

Parents can help by establishing predictable routines, setting clear expectations, using positive reinforcement, minimizing distractions, promoting emotional regulation, and seeking professional help when necessary.

The strategies below offer practical, evidence-based tips for parenting a child with ADHD in everyday situations.

Nutrition, Movement, and Sleep in ADHD

No diet cures ADHD. However, balanced nutrition, regular physical activity, and consistent sleep routines can significantly support attention, emotional regulation, and overall well-being.

- Children with ADHD often struggle with irregular eating patterns. Skipping meals, forgetting to eat, or overeating later in the day are common behaviors, especially when there is no structure in place. Offering regular, nutritious meals or snacks every two to three hours helps maintain stable energy levels and reduces irritability and emotional dips.

- Physical activity plays an important role in managing ADHD symptoms. Regular movement helps release excess energy, improves focus, reduces anxiety and low mood, and supports healthy brain development. Activities do not need to be intense to be beneficial; consistency is more important than intensity.

- Sleep is another critical factor. Many children with ADHD experience difficulty settling at night or maintaining regular sleep patterns. A consistent, early bedtime routine is one of the most effective ways to support sleep quality, which in turn improves attention, mood, and daytime functioning.

Rather than focusing on perfection, small, predictable routines around eating, movement, and sleep often make the biggest difference.

Practical Parenting Scenarios: How ADHD Shows Up in Real Life

Understanding ADHD in theory is one thing. Parenting a child with ADHD day after day is another. Even when parents understand the definitions and symptoms, they still struggle when those symptoms intersect with real-life moments, such as mornings, homework, transitions, social situations, and emotional meltdowns. Here are some behavioral strategies to help manage your child's ADHD.

Morning Routines With a Child With ADHD

Mornings are one of the most challenging times for families with a child with ADHD. Getting dressed, brushing teeth, packing a bag, and leaving the house on time require attention, sequencing, and emotional regulation, all of which are areas impacted by ADHD.

A child with ADHD may:

- get distracted mid-task

- forget the steps they have done every day

- become overwhelmed by time pressure

- react emotionally when rushed.

Parents often interpret this as resistance or laziness, but it is usually a difficulty with initiating and completing tasks.

Helpful strategies include:

- Creating a visual morning checklist.

- Lying out clothes and school items the night before.

- Using timers to externalize time.

- Reducing verbal reminders and using visual cues instead.

Supporting a child with ADHD during mornings is about reducing cognitive load, not increasing pressure.

Homework and Task-Related Challenges

Homework is another frequent source of conflict. Often, children with ADHD understand the material but struggle to sit down, stay focused, and complete tasks independently.

Common difficulties include:

- Trouble starting homework

- Losing focus partway through

- Becoming emotionally overwhelmed

- Avoiding tasks that feel boring or difficult

Parents can help by breaking homework into short intervals, offering structured breaks, and sitting nearby for support without taking over. The process of completing tasks improves when expectations are clear and the environment is supportive.

Emotional Dysregulation and Meltdowns

Emotional dysregulation is a core feature of ADHD. Children with ADHD often experience emotions more intensely and have difficulty calming down once upset. During moments of high emotional arousal, skills like impulse control, flexible thinking, and self-control are temporarily unavailable.

Meltdowns are more likely to occur:

- after school, when the child is overstimulated

- during transitions

- when expectations are unclear

- when the child feels criticized or misunderstood.

During emotional outbursts, reasoning rarely helps. Behavioral training emphasizes co-regulation first, correction later. Calm presence, emotional validation, and support are far more effective than explanations or consequences in the heat of the moment.

Behavioral strategies are most effective when they are planned and practiced outside of meltdowns. A points system can be used to reinforce specific, observable behaviors before emotions escalate, such as starting tasks on time, transitioning calmly, or using words instead of outbursts.

Time-outs, when used, should be brief, predictable, and non-punitive. Ideally, time-outs can be understood as a regulated break from stimulation, not isolation or loss of connection. They should never involve withdrawing affection or shaming. A supportive time out might sound like:

“Your body looks overwhelmed. Let’s take a short break together, and we’ll talk once things feel calmer.”

Once the child has settled, parents can help reflect on what happened and practice alternative responses for next time.

Social Skills and Peer Relationships

Children with ADHD may struggle with socializing due to impulsivity, interrupting, difficulty reading social cues, or emotional reactivity. These challenges are rarely intentional, but they can make forming and maintaining friendships more difficult.

Social difficulties often show up as talking over others, missing subtle cues, reacting strongly to teasing, or struggling with turn-taking. Over time, this can affect friendships and self-esteem, especially if a child feels frequently corrected or excluded.

Parents can support social development in practical ways:

- Practice social skills outside of the moment.

Role-play common situations, such as joining a game, waiting for a turn, or handling disagreement. Practicing when emotions are calm makes it easier to apply skills later. - Offer gentle, specific coaching.

Instead of broad feedback like “be nicer,” try concrete guidance such as, “Let’s practice waiting until your friend finishes talking.” - Choose environments that support success.

Smaller groups, shared-interest activities, or one-on-one playdates are often easier than large, unstructured settings. - Focus on strengths.

Encouraging activities that match the child’s interests can help them connect with peers more naturally and build confidence.

Managing Screen Time With ADHD

Screen time can be especially stimulating for children with ADHD. Fast-paced content, rapid rewards, and constant novelty may increase impulsivity and make it more challenging to transition away from screens.

Rather than banning screens entirely, which often leads to power struggles, a structured approach is usually more effective.

Helpful strategies include:

- Set clear screen time limits in advance.

Let children know when screen time starts and ends, and keep limits predictable. - Use transition warnings.

Provide reminders, such as “10 minutes left” or “one more episode,” which help children shift their attention gradually. - Avoid screens close to bedtime.

Reducing screen use before sleep supports better rest, which directly affects attention and emotional regulation the next day. - Link screens to routines, not emotions.

Screens work best when they are part of a routine, rather than being used to calm distress or reward emotional outbursts. Consistency matters more than strict rules. Predictable screen routines reduce conflict and help children adjust expectations over time. In addition to structured routines and screen time limits, parents may find other practical strategies helpful in improving focus with ADHD, which can help manage attention and reduce distractions in everyday activities.

Supporting Behavior Without Punishment

Traditional punishment often backfires in ADHD parenting. Because impulsivity and emotional dysregulation are neurological, punishment alone is insufficient to teach self-control or alternative behaviors.

More effective approaches focus on guidance, structure, and reinforcement, rather than consequences delivered in frustration.

Parents can support behavior by:

- Setting clear, simple expectations.

Children with ADHD tend to perform better when expectations are clear and stated in advance. - Using consistent, predictable consequences.

Follow-through matters more than severity. Calm consistency builds trust and understanding. - Prioritizing positive reinforcement.

Children with ADHD often receive far more correction than praise. Actively noticing effort, progress, and appropriate behavior helps balance this. - Teaching alternative behaviors.

Instead of only pointing out what not to do, show and practice what to do instead, such as asking for help, taking a break, or using words.

Final Encouragement for Parents

Parenting a child with ADHD can be emotionally demanding. Chronic stress, self-doubt, and exhaustion are common, not because parents are doing something wrong, but because the demands are real and ongoing. Parents of children with ADHD often experience increased stress and anxiety, making self-care even more crucial. Parenting a child with ADHD when you have ADHD yourself can intensify stress and emotional fatigue, making structure, external support, and self-compassion especially important.

Self-care is vital for parents of children with ADHD to maintain their own emotional and physical health. Taking breaks is essential to recharge and avoid burnout when caring for a child with ADHD. Parents should prioritize their own health by eating right, exercising, and managing stress to effectively support their ADHD child.

💛 Caring for yourself is not selfish. When parents feel steadier, children benefit from calmer, more responsive support.

Additional resources for parents:

- CHADD is a leading organization that provides education, advocacy, and local support for ADHD.

- HealthyChildren.org offers articles and behavior therapy information specifically for ADHD.

- Parents can connect with other parents of children with ADHD for moral support and practical tips.

- Hotlines and helplines are available for parents seeking support for ADHD-related issues.

- Books on parenting a child with ADHD can also be helpful, especially those grounded in behavioral parent training and neurodevelopmental research.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (n.d.). Nutrition: Healthy living. HealthyChildren.org. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/healthy-living/nutrition/Pages/default.aspx

- American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). What is ADHD? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/adhd/what-is-adhd

- Barkley, R. A. (2015). ADHD, executive functions, and self-regulation. https://www.russellbarkley.org/factsheets/ADHD_EF_and_SR.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). ADHD data and statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/adhd/data/index.html

- Faraone, S. V., Biederman, J., & Mick, E. (2015). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 57(11), 1215–1220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.09.010

- National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd

- Theule, J., Wiener, J., Tannock, R., & Jenkins, J. M. (2013). Parenting stress in families of children with ADHD: A meta-analysis. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 21(1), 3–17. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1063426610387433

- Toplak, M. E., Dockstader, C., & Tannock, R. (2006). Time perception deficits in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(8), 888–895. https://acamh.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01428.x

FAQ: Parenting a Child with ADHD

What are the most common ADHD symptoms in children?

How is ADHD diagnosed in children?

Can a child with ADHD behave well sometimes?

How does ADHD affect a child’s self-esteem?

What parenting strategies help children with ADHD the most?

How can parents support a child with ADHD at school?

Does screen time make ADHD worse?

Is ADHD medication always necessary?

Can children with attention deficit disorder succeed later in life?

When should parents seek professional help with ADHD parenting?