What Is Anxiety and What Does It Feel Like?

Anxiety is our natural alarm system: a set of feelings, body sensations, and thoughts that signal something in our world needs attention. It becomes an anxiety disorder when the fear and worry are persistent, excessive, and get in the way of everyday life.

Most of us experience occasional anxiety. We've all felt that tight knot in the stomach before an important speech, the restless night before a big move, or the jittery feeling while waiting for test results or going on a first date. Occasional anxiety is a natural response to stress, uncertainty, or actual danger, and in small amounts, it helps us prepare and act. But when worry becomes a constant background noise rather than an occasional visitor, the pattern may fit what clinicians describe as an anxiety disorder.

The goal of this article is to help you recognise the difference between a natural anxious response and excessive anxiety, understand common types of anxiety disorders, and learn where and how to look for support.

Key Learnings

- Anxiety is a natural response to potential stress or change. Still, it can turn into a clinical anxiety disorder when the worry becomes persistent, often most days for six months, and starts disrupting daily life.

- Symptoms of anxiety can be both emotional (persistent and excessive worry, intrusive thoughts, difficulty concentrating) and physical (rapid heartbeat, chest pain, sleep problems, muscle tension).

- There are many types of anxiety disorders, from generalized anxiety disorder to social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, OCD, phobias, and separation anxiety disorder, and each has its own different features and appropriate treatments.

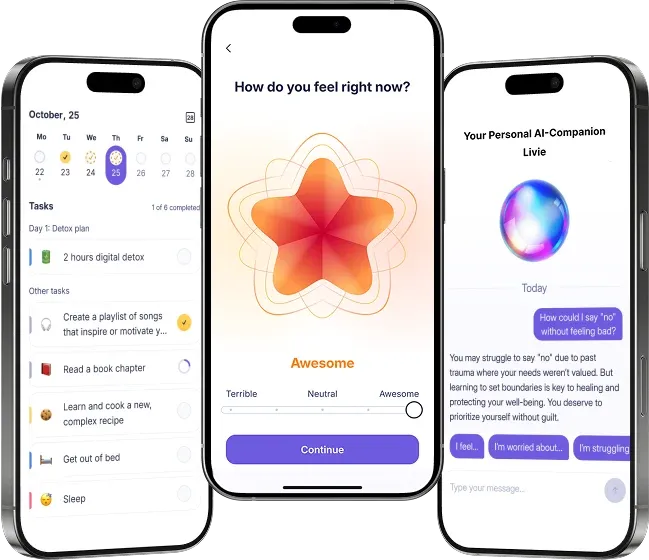

- Effective treatments include talk therapy, medications, lifestyle changes, and support groups. Utilize tools like mood trackers (e.g., Liven app) and journaling to identify patterns and support your therapy.

Symptoms of Anxiety

Anxiety can show up both in the mind and the body. People with anxiety disorders often describe the experience as a loop: worries feed physical symptoms, and physical symptoms feed worry and rumination.

Emotional and Cognitive Symptoms of Anxiety

- Persistent and excessive worry about everyday concerns (work, family, money).

- Intrusive thoughts that are hard to dismiss, a sense of impending doom, or intense fear around particular situations.

- Difficulty concentrating or blank mind, memory issues, and distractibility. These cognitive effects make it harder to work or study.

- Irritability, avoidance of situations, or feeling constantly “on edge.”

Physical Symptoms of Anxiety

- Rapid heartbeat (palpitations) and chest pain or tightness — symptoms that can sometimes mimic heart problems.

- Shortness of breath, sweating, trembling, or shaking.

- Sleep disruption (trouble falling asleep, frequent awakenings, nightmares) and fatigue.

- Digestive symptoms like nausea, diarrhoea, or worsened IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome).

- Muscle tension, headaches, and other somatic complaints.

💡 If you feel anxious and notice these symptoms most days for weeks or months, it’s worth checking in with a mental health professional, as these are common symptoms of anxiety disorders and can respond well to treatment.

Causes and Risk Factors of Anxiety

Anxiety rarely has a single cause. A mix of biology, life events, and learned responses typically combine to create anxiety symptoms.

Anxiety disorders are often chronic, impair functioning, and involve a combination of cognitive, physiological, and situational factors.

- Biological and medical contributors

- Family history and genetics make some people more vulnerable to anxiety disorders.

- Research suggests that neurotransmitter systems, including GABA, serotonin, and norepinephrine, play a role in how reactive the nervous system becomes. These systems don’t “cause” anxiety on their own, but they help shape how strongly the body responds to stress.

- Medical conditions (thyroid disease, cardiac conditions, respiratory problems, diabetes), and even withdrawal from substances, can trigger or worsen anxiety.

- Psychological and social contributors

- Past traumatic events and unresolved traumatic events increase the likelihood of developing anxiety or PTSD-related symptoms.

- Chronic life stress, grief, parenting pressures, job insecurity, and prolonged uncertainty may dysregulate stress-response systems (HPA axis) and lead to persistent anxiety.

- Certain personality traits (e.g., perfectionism) or early life attachment patterns can be risk factors.

3. Environmental triggers

- Life events such as relationship breakdowns, loss, moving countries, or major life changes often trigger or amplify anxiety.

- Substance use, sleep deprivation, and excessive caffeine can worsen anxiety and make panic attacks more likely.

For many people, anxiety and overthinking travel together. If that sounds familiar, this guide on why we overthink may help you understand the cycle.

💛 All of these are risk factors rather than destiny: they change probability, and they point to treatment targets (medical review, therapy, or lifestyle change).

Types of Anxiety Disorders

There are several common types of anxiety disorders; each has its own typical pattern of worries and behaviours.

The NIMH identifies generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and various phobia-related disorders as the most common anxiety disorders.

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) — constant worry about many aspects of daily life, often accompanied by muscle tension, sleep disturbance, and fatigue. A worry loop that’s both pervasive and costly to daily functioning.

- Social Anxiety Disorder (previously called social phobia) — intense fear of being judged or embarrassed in social situations that can be crippling for work and relationships. Social anxiety commonly begins in adolescence and is more common among people who fear negative evaluation.

- Panic Disorder and Panic Attacks — sudden episodes of intense fear that peak quickly, often with chest pain, rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, and a sense of losing control. Many people with panic disorder develop a fear of future panic attacks and may start avoiding places where attacks have occurred.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) — intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviours (compulsions) performed to reduce distress. OCD can consume hours each day for some people.

- Specific Phobias — extreme fear of a particular object or situation (spiders, needles, flying) that leads to avoidance.

- Separation Anxiety Disorder — excessive fear about separation from attachment figures; common in kids but can persist into adulthood and cause marked impairment.

- Other Anxiety Disorders include selective mutism (persistent failure to speak in social situations despite normal language skills in different contexts), and anxiety presentations linked with medical conditions or substance use.

If your concern is a mix of anxiety and depression, it’s common for the two to co-occur, an anxiety and depression association that clinicians watch closely because treatment may need to address both.

How Clinicians Diagnose Anxiety Disorders

Diagnosis is not a single test; it’s a process. A clinician will usually combine:

- A focused clinical interview about symptoms and functional impact.

- A review of medical history and possible lab tests (thyroid, blood sugar) to rule out physical contributors.

- Standardised screening tools (GAD-7, HAM-A, BAI) and diagnostic criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) used by the American Psychiatric Association.

- Observation of symptom patterns (duration, intensity, triggers) to decide which type of anxiety disorder best fits.

Self-screening tools are helpful first steps, but they should be interpreted in conjunction with your medical history by a mental health professional.

Evidence-Based Treatments: What Helps Anxiety Disorders

There’s no single fix for anxiety disorders because no two nervous systems are wired the same way. But we do have well-researched, science-backed treatments that help people with anxiety disorders feel better, function better, and understand themselves better.

Think of them as tools. Some sharpen the mind, some calm the body, and some help you soften toward your inner world; most people benefit from a combination.

Talk Therapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

A large 2022 meta-analysis found that CBT produces substantial and lasting reductions in anxiety symptoms. However, for many people, CBT reduces symptoms quickly.

However, symptoms can return just as quickly if deeper layers aren’t addressed. Anxiety isn’t only a thought problem; it’s also a nervous-system pattern, a history pattern, and sometimes a trauma pattern. When CBT is combined with other approaches that address the body and the emotional roots, its effects last much longer.

Exposure Therapy

A major review found that exposure therapy is one of the most effective and well-supported treatments for anxiety disorders, helping people relearn safety by gradually facing the situations they fear.

However, exposure works best when it’s done gently, collaboratively, and with attention to the body, rather than as a “white-knuckle your way through it” exercise.

ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy)

ACT (sometimes called “commitment therapy”) teaches you how to live with anxiety without letting it control your actions. It’s especially helpful for chronic worry and rumination because it focuses on values, flexibility, and making space for discomfort instead of fighting it.

A large meta-analysis found that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) effectively reduces anxiety symptoms across a wide range of conditions by helping people respond more flexibly to difficult thoughts and emotions.

ACT carries a simple but powerful idea. As psychologist Steven Hayes says, “You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf.”

Trauma-Informed Therapies

Sometimes anxiety grows from places that CBT alone can’t reach, such as the body’s long-held memory of overwhelm, early relationships, or traumatic events that shaped how we protect ourselves.

Trauma-informed approaches like EMDR, somatic work, and polyvagal-informed therapy could help the system calm down from the inside out. They don’t just quiet the thoughts; they help the body find safety again.

Trauma specialist Bessel van der Kolk reminds us that “the body keeps the score,” which is why anxiety rooted in trauma often needs body-based and somatic approaches.

Medications

For some people, especially those dealing with severe anxiety or panic attacks, medication can be an important part of treatment. Antidepressants (like SSRIs or SNRIs) are commonly prescribed for anxiety disorders and are well studied. Short-term medications can help in acute phases, but long-term use needs careful monitoring.

Medication isn’t a cure, but for many, it creates enough stability to actually use the therapeutic tools.

Lifestyle & Daily Practices

This is the part that doesn’t often get the spotlight, but it’s crucial:

Anxiety decreases when the nervous system has reliable routines.

Things that might help reduce anxiety and keep symptoms from returning include:

- consistent sleep

- steady and nutritionally balanced meals

- breathwork and grounding

- movement

- reducing stimulants

- support groups

- community and friends

- a spiritual or contemplative practice

- working with art, expression, and body

- journaling and mood tracking to catch patterns early

Tools like Liven’s Mood Tracker, structured micro-practices, and personalized journeys help people with anxiety disorders build those stabilizing habits day by day.

The Honest Bottom Line

Anxiety disorders are treatable, but no therapy works in isolation. CBT works. Exposure works. ACT works. Trauma-informed therapies work. Medication works for many.

But the most lasting change happens when you combine:

- the mind

- the body

- daily patterns

- the story your nervous system has lived through

That’s where symptoms ease, confidence returns, and the signal of fear finally turns down.

Please seek urgent help if anxiety is accompanied by:

- Chest pain, fainting, or severe breathlessness (medical review needed).

- Thoughts of harming yourself or others (emergency help).

- Rapid functional decline at work or in relationships.

Severe anxiety and panic attacks deserve rapid assessment because they impair functioning and can worsen other health issues.

Practical Next Steps: How to Be With Anxiety

- Start with a brief self-check (GAD-7) and a mood log in the Liven app to record trigger patterns and symptoms.

- Book a primary care or mental health appointment to review your medical history and rule out any physical causes.

- Try daily stress management techniques for immediate relief, such as paced breathing, taking walk breaks, and maintaining consistent sleep.

- Consider talk therapy as a first-line psychological treatment. If medication is needed, a clinician will discuss anti-anxiety medications and monitor effects.

- Use a structured tool to support change. If you'd like a guided starting point, take Liven’s quick quiz to receive your personalized plan for a calmer mind.

Long-term Outlook: Recovery and Healing

Many people with anxiety disorders do get better, and not in this "big white light" sudden cinematic moment, but instead, in small steps that build a life that feels more spacious and possible again.

Recovery is less about “never feeling anxious” and more about knowing what to do when anxiety shows up. Over time, therapy, medication when needed, and daily habits create a kind of inner muscle memory: your nervous system remembers how to settle, how to breathe, and how not to believe every spike of fear.

With practice, you start to notice early signs before anxiety grows teeth. You learn when to slow down, when to reach out, and when to let your nervous system settle instead of spiralling.

That’s resilience: not perfection, but the ability to find your way back, again and again, with growing ease.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm

- A-Tjak, J. G. L., Davis, M. L., Morina, N., Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A. J., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2015). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(1), 30–36. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25547522/

- Bandelow, B., Michaelis, S., & Wedekind, D. (2017). Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 19(2), 93–107. (Used for general anxiety risk + personality factors.) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28867934/

- Craske, M. G., Treanor, M., Conway, C. C., Zbozinek, T., & Vervliet, B. (2014). Exposure therapy for anxiety disorders: A review. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 58, 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.004

- Hayes, S. C. (2005). Get Out of Your Mind and Into Your Life. New Harbinger Publications. https://www.newharbinger.com/9781572244252/get-out-of-your-mind-and-into-your-life/

- Kessler, R. C., Sonnega, A., Bromet, E., Hughes, M., & Nelson, C. B. (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52(12), 1048–1060. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7485629/

- Lehrer, P. M., Kaur, K., Sharma, A., Shah, K., Huseby, R., Bhavsar, J., Sgobba, P., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Heart rate variability biofeedback improves emotional and physical health and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 46(4), 199–233. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32385728/

- Levy, D. R., Boulanger-Bertolus, J., et al. (2022). Serotonin and anxiety: Complex relationships. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35026465/

- Longo, L. P., & Johnson, B. (2000). GABAergic mechanisms in anxiety. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(3), 717–728. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10972580/

- Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Anxiety: Symptoms & causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anxiety/symptoms-causes/syc-20350961

- National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Anxiety disorders. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders

- Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009

- Roy-Byrne, P. P., Davidson, K. W., Kessler, R. C., Asmundson, G. J. G., Goodwin, R. D., Kubzansky, L., Lydiard, R. B., Massie, M. J., Katon, W., Laden, S. K., & Stein, M. B. (2008). Anxiety disorders and comorbid medical illness. General Hospital Psychiatry, 30(3), 208–225. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18433653/

- Southwick, S. M., Bremner, J. D., Rasmusson, A., Morgan, C. A., Arnsten, A., & Charney, D. S. (1999). Role of norepinephrine in the pathophysiology and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 46(9), 1192–1204. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10560025/

- Twohig, M. P., & Levin, M. E. (2017). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy as a Treatment for Anxiety and Depression: A Review. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 40(4), 751–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.009

- Van der Kolk, Bessel. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Anxiety disorders — Fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/anxiety-disorders

- Yunitri, N., Kao, C.-C., Chu, H., Voss, J., Chiu, H.-L., Liu, D., Shen, S.-T., Chang, P.-C., Kang, X.-L., & Chou, K.-R. (2020). The effectiveness of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing toward anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Psychiatric Research. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32058073/

FAQ: What is Anxiety?

What is anxiety vs. a normal reaction?

How are anxiety disorders diagnosed?

What is Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)?

How do you treat anxiety disorders?

Are panic attacks the same as panic disorder?

Can anti-anxiety medications help?

What is social anxiety disorder or separation anxiety disorder?

How do anxiety and depression relate?

Can lifestyle changes relieve anxiety?

How does anxiety show up in children, and what are selective mutism and separation anxiety?